In this section, I go over basic symbolic interactionist theory and then emphasize the neglected but central innovation of George Herbert Mead—the generalized other. After presenting an overall model of symbolic interaction including Erving Goffman’s front and backstage, I then show how this model leads to a theory of structure, which symbolic interactionists tend to avoid.

The Basic Theory

Mead (1934) presents a theory of social psychology that involves a theory of the mind and a theory of social interaction that produces a self.[1] With a specific form of identity and purpose in life. I will present this in two stages: (1) the general version of the theory using some aspects of Erving Goffman and multiple selves in the process in this section, and (2) a version of the theory that gives much more emphasis to the generalized other as the building block of positive and negative group relations in the next section.

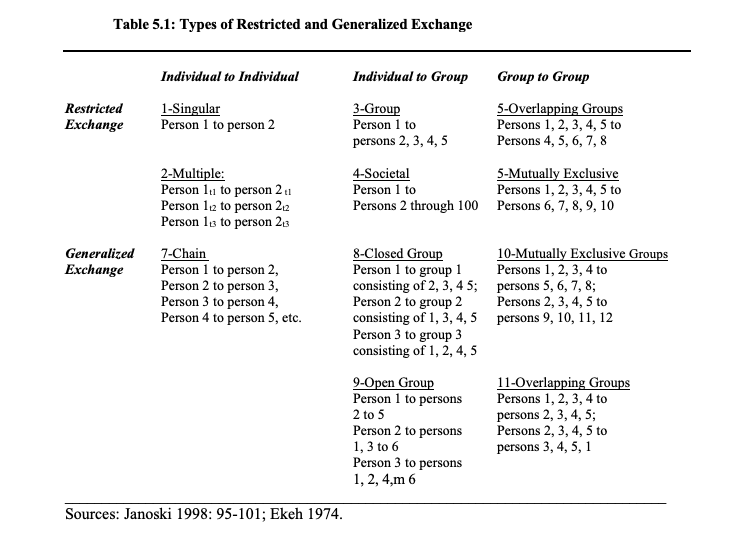

The first step in this section is the overall model which will be a bit different from standard accounts but builds on Jonathan Turner’s view of G. H. Mead (1988: 73-84) and Erving Goffman (1988: 86-101).[2] In Figure 5.1, the overall process is described.

Political sociology is largely an adult interaction rather than how child is socialized, so I will start with the self-concept already formed in item 1, but posit that we all have multiple selves that are often attached to the different network roles that we have in society. Our self as a parent may differ in many ways from our self as a manger, worker, or professional in our jobs.[3] We may differ in our friendship groups. Each of these selves monitor situations in item 2 in order to determine what they need to do to survive and prosper in society. In doing so, the “I” in item 3 strategically determines what actions to take and more specifically selects different “me’s’ in item 5 to present in various appropriate situations. In order to make these presentations of self (Goffman), each person will “stage” in item 4 those presentations with various props, ritual sequences, specific scripts, and so forth using Goffman’s sense of dramaturgy. The presentation then ends with some specific types of action in item 6, and by means of Weber, the action may take place out of habit, following tradition, involving some emotion, and/or through some sort of calculation via various types of rationality (most basically through value or instrumental rationality) (Kalberg 1980).

Those performances in interaction with others (an audience) lead to their feedback to the “I” and “Me,” through the generalized other (i.e., Cooley’s ‘looking glass self’) and people react to this feedback via the generalized other in adjusting their future presentations of self in that same interaction and/or in future interactions. The generalized other is further constructed by each person in items 6, 7 and 8. The reactions or reflected appraisals have to be interpreted by the self or often the ‘I’ and they are accurate or somewhat biased in these interpretations. The “I” has a strong tendency to try to appraise other’s reactions in a positive way in order to reinforce self-esteem. However, as these biases may contradict further interactions, the generalized other is often corrected (“I thought you were my friend, but now I know otherwise”, or “I thought you disliked me, but now I realize I was mistaken”). Thus, in item 8, the generalized other feedback is selected, framed, and ranked for the “I” so that it can be correctly but iteratively perceived. These processes of the generalized other have been generally ignored by symbolic interactionists, although Margaret Archer (2003) with her emphasis on the “internal conversation” comes the closest to approximating it though she criticizes Mead’s description of the concept.[4]

The generalized other as seen as the major innovation of George Herbert Mead’s social psychology. The “I” and “Me” had been seen in other theories (William James, for instance), but the generalized other was new. It is subject to a number of controversies. On the one hand, some say that the “other” is generalized so much that it represents a person’s unified view of how society, as a whole, views a person’s sum total of actions. As a result, the generalized other is the sum of perhaps thousands of feedback loops that give us an idea of how we should act in society. I contend that the generalized other is more context specific in that generalized others tend to develop according to network and role situations, not ruled by them, but socially constructed by each person. Hence, there are multiple generalized others that become entwined with multiple selves. Situations are neither unique, nor totally predictable. Instead, each situation is constructed according to the group and situational constraints.

The other problem with the generalized other is that some (Archer 2003) contend that the generalized other as presented by Mead can be seen as deterministic. We present a “Me” to others, and then the feedback tells us that we succeeded, we failed, or we were ignored. As a result, we more or less orient our future actions according to what the generalized other “tells us to do.” However, this erases the impact of the “Me’s” on the generalized other and makes the “I” a relative automaton or simply a mirror of the generalized other. This is also not the case. Clearly, the “I” in determining what “Me’s” to present may continue to oppose or persuade its audience and generalized other in another direction. There is variation as some people are ruled by what others think, and others, especially the mentally ill, may totally ignore the thoughts and reactions of others. But as Donald Tomaskovic-Devey and Dustin Avent-Holt say “even the smallest person has some gravitational pull” (2019:227). Some may be opinion leaders who sway their generalized other, and other’s hesitancy or reluctance may hold back a generalized other from strong reactions. Thus, the generalized other is subject to variations of agency and not an unopposable force.

Hence, the “I” is neither encompassing all of society in every interaction by an ‘overly generalized’ other, nor is the generalized other the ‘commander’ of every self through its deterministic pronouncements in the mirror of one’s actions. Nonetheless, the conventional view of symbolic interaction tends to downplay the generalized other and it is Mead’s great discovery of the social. But then it almost disappears from symbolic interaction theory and empirical practice. Everyone wants to talk about “the self” and even some jump to “identity” as if it were permanently imprinted upon one. In the next section, I will problematize the generalized other and expand its role in symbolic interactionist theory. Some symbolic interactionists, object to this and say why should you complicate a perfectly good theory, but I shall respond that one needs to delve more deeply into how people view others and construct their political selves.

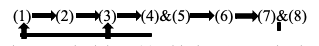

Figure 5.1 may seem like it is complex with nine parts and many arrows, but most of the time people do not go through all of these steps. There are three distinct patterns that occur: totally reflexive, partially reflexive, and not reflexive. First, totally reflexive social action goes through all the stages in figure 5.1:

In most cases the return look is to (3) with the ‘I’ re-evaluating the events and outcomes. In the longer and less frequent process, a person goes through the full sequence of thinking everything out by going back to first principles about the self in (1) and monitoring situations with care in (2). Further, the generalized other is fully thought out after the social act and framed according to different generalized others in terms of being positive or negative. This is a mostly rational process with the more formal rationalities (procedural and theoretical) but we should keep in mind that all actions still have emotions or traditions even though they may play a small part (Kalberg 1980). For example, when a white person is faced with the injustices of the ‘black lives matter’ movement and takes to heart the killings that occur, he or she may question “what kind of person am I?” They may then seek to create a different self that reconstructs their monitoring, presentations of self, and social actions; and after the act, they reconstruct their generalized other. And this process may require a number of interactions before one might be satisfied with the result. Some interactions may take place repetitively in the mind with what Margaret Archer refers to the “internal conversation”:

This ‘soul searching’ or ‘self and generalized other’ searching takes deliberation, thought and considerable care, but it does not actually present a self (e.g., get to stage 4 and 5).

Second, people cannot possibly go back frequently to first principles of the nature of their self. Since the decision-making burdens of the first process are great, they take short-cuts. Most of the time, people use partially rational and partially reflexive processes. This looks like:

In this partially rational process people use practical and/or value-oriented rationality which is less taxing than procedural and theoretical rationality (Kalberg 1980) coupled with emotional and traditional action (Weber 1978). This is probably the most common form of social action with a moderate amount of thought in choosing social actions with some accounting for the reactions of other people and little or no re-evaluation of one’s multiple selves. For example, in making judgements about what political causes to contribute to, the ‘I’ rationally considers alternatives based on what they have done in the past. The ‘I’ selects the actions that generally satisfy their sense of self and generalized others that they interact with, and make a decision. Emotions and traditions are more involved. They take these short cuts to avoid the paralysis that Professor Chidi Anagonye in The Good Place experiences when he overanalyzes every moral situation he faces with the end result that he can never (until the end) decide. This, of course, equally infuriates his friends and acquaintances.[5]

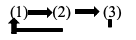

Third, the non-reflexive position uses the most emotion and traditional action. It short-circuits many of the processes of deliberation and is a sense like operating on automatic. It is shown as:

![]()

![]()

This is more similar to Weber’s conception of habit or conventions. The ‘I’s role is minimal though it may be involved in some unconscious or subliminal way. The emotions and traditions tend to take over and the social action is either reflected in the generalized other or this stage can also be skipped. This response can go further as George Herbert Mead refers to it as the “fusion of the ‘I’ and the ‘Me’” that leads to stereotypes like nationalism, racism, sexism, and other automatic responses (actually, Mead only mentions nationalism but the extension fits his theory).

Nonetheless, we all have habitualized parts of our lives which we think do not require any extensive thought. How often have we driven to work without deciding about the route, and sometimes, not even remembering the route. Nonetheless, we can establish personal habits about cleanliness or driving, but should be extremely careful about habitualizing thoughts about whole categories of people or in new situations like the Great Recession of 2008 or Covid-19 in 2020 to 2021.

The Multiple Me’s and Generalized Others as the Initial Route to Structure

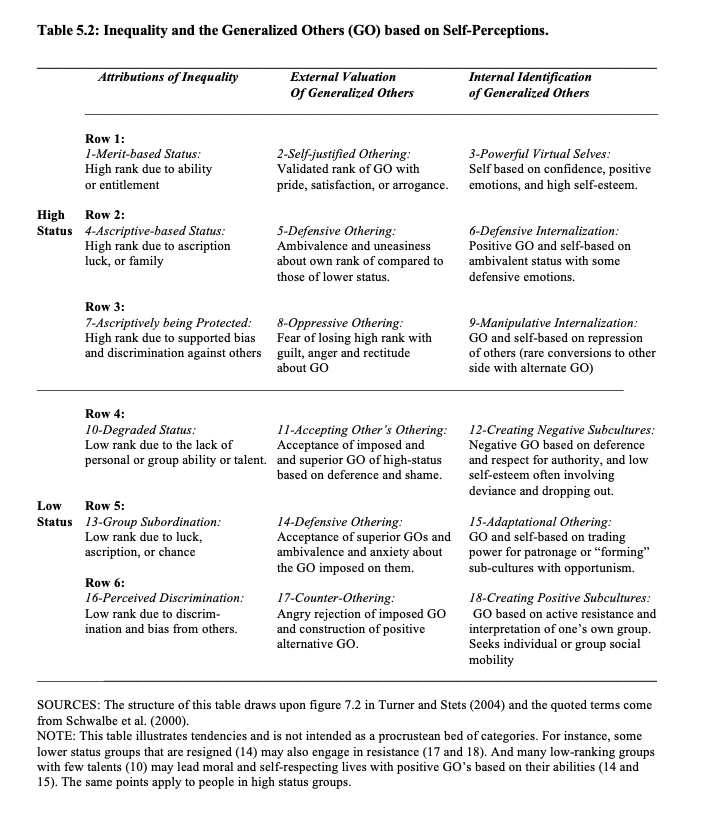

The generalized other is more complex and important than symbolic interactionists have previously thought. In this sense, I take more after W. E. B. DuBois concept of ‘dual consciousness’ and especially the fact that there are multiple generalized others and that they may be positive or negative. In other words, one generalized other might be friendly and supportive and the other might be hostile and threatening. The general model for the “Me’s” and the “generalized others” was shown in Figure 5.1. Most social psychology now recognizes that there are multiple identities involved with most people (Markus and Wurf 1987). Some view this as intrinsic to modernity, but using more conventional theory, as much as anyone plays multiple roles in society they develop multiple identities and ways of acting in those roles. In more symbolic interactionist theoretical terms, they view the generalized other as one item, but I view it as two items (7 and 8). In items 1 through 5, multiple selves monitor situations with the “I” choose multiple “Me’s” to present in different interactions with others. In item 6, I add the Weberian forms of social action in terms of emotional, traditional and rational action. Much social action is traditional in terms of habits and conventions. Emotional action often occurs with tradition, but it becomes intensified when the traditions are broken. In many cases tradition itself is a rational action, but new rational actions often come about when society is disrupted (Durkheim) but also disruption can be created by rational action (Marx). Rationality can also be viewed at various levels of abstractions. One might be rational at the substantive and procedural level in their personal actions but be at the processual or theoretical level when trying to pursue some larger political, economic or cultural change (Kalberg 1980; Janoski 1998).

The actions that result from each “Me” in item 8 are then fashioned into multiple “generalized others” or “GO’s” that are communicated back to the “I” from item 8 to item 3 or sometimes feedback can be entertained midstream in a performance of the “Me” from item 8 to item 5. Usually, the reflected appraisals of each “Me” take place in different situations often with different roles. So, a particular “Me1” is presented in one’s home with family, another particular “Me2” is presented at school, and yet another “Me3” at work with strangers or acquaintances. These performances are evaluated by the members of the group that they interact with, and each person constructs a positive, neutral or negative generalized other. These constructions can be quite variable with some being created in an accurate manner or others highly biased. In Figure 5.2, I examine four different people from studies that I have done with Chrystal Grey (2014) and Darina Lepadatu (2010).

In an ethnography of assembly workers, Anna Gibson at a Japanese transplant in the US has positive GO1 which consists of the close relations with her team members with whom she works long hours as her the top generalized other closely followed by her larger group GO2. More generally, other men at work form a negative generalized other GO4 and women in her neighborhood and some of her family, especially men, criticize her for her long working hours. Janine Johnson, who advanced to a machine tool maker at a GM auto plant in the 1970s, finds both men and women at work highly critical of her to the point suffering catcall yelled out by men and a lack of cooperation from them in doing her job. The hours at work were not as long as the Japanese transplant so her family is grateful for the pay. So she had no positive generalized other at work at all (Lepadatu and Janoski 2008).

In a study of Afro-Caribbean and African American mobility, two academics Professor Burton Brenn and Provost Dorothy Smythe constructed their generalized others much like DuBois might expect (Grey and Janoski 2018). Professor Burton constructs an ‘identification others’ or “We’s” who are relatively positive toward him: GO1 consist of his Afro-Caribbean friends and family, and GO2 involves people in a multi-racial church to which he belongs. The other two are somewhat more negative: GO3 consists of white and Afro-American acquaintances who generally view his mobility as good or neutral. However, some whites are resentful of his success and they engage in negative reactions (GO4). Dean Smythe is similar in half the instances, but different in that she has a white generalized other that supports her (GO2), and black generalized other that criticizes her for “acting white” (GO3), which is an instance or ressentiment. The Dean’s first and last generalized others (GO1 and GO4) are the same as Professor Burton Brenn though her positive generalized other is composed of Afro-Americans rather than Afro-Caribbeans (Grey and Janoski 2018).

In DuBois’ terms, the generalized other is stark with the black and white generalized others, which are clearly opposed to each other with the incredibly divisive “color line” of the late 1800s and early 1900s. Yet this seminal theoretical opening shows the way for not only multiple generalized others, but also positive and negative generalized others for all people in society (Holdsworth and Morgan 2007: 408; da Silva 2008; Blumer 2004). Everyone who interacts in society faces people who promote or encourage them and others who oppress or oppose them. The degrees of promotion and oppression may vary quite a bit, but they are present in each of us and we generalize about these groups to negotiate our ways through life (Strauss 1978). This does not mean that people always interact in a strategic way that rational choice theory suggests. Instead, we understand which generalized other characterizes our interactions and engage in either Mead’s idea of ‘sociation’ with positive generalized others often with generalized exchange, or Goffman’s sense of ‘strategic interaction’ with competitors or negative generalized others with restricted exchange.

The route to structure comes from the fact that we know how our generalized others are connected to other people. There are two principles here. First, the positive generalized others consisting of those we have face-to-face or direct internet conversations with are generally in the range of small groups. But we know that these people have their own generalized others that extend to people we do not interact with often. Nonetheless, we may expect positive experiences with our extended kin or friends of friends. Similarly, with negative generalized others we surmise that we might not be welcomed. For African-Americans, expectations of interacting with indirect whites would be approached with a certain amount of caution. Second, there is a certain amount of overlap between our generalized others. We know some of the people in one generalized other may be in another of our generalized others. For instance, our neighbor may also be in the Parent Teacher Association (PTA) at our children’s school, and a workmate may go to our church, temple or Mosque. In tightly knit communities like recent immigrants, some may all live and work at the same locations. For others more dispersed in society, the overlap is less but nevertheless present to varying degrees. For this information, individuals construct a “sense of group position” (to be discussed in the next chapter in more detail) such that they form a sense of social structure of their direct and indirect network connections (Blumer 1958). For those who are socially astute or social mobility oriented, these mental maps of structure may be quite elaborate. For most others, it is a form of tacit knowledge that they do not formally erect but they may draw on it when someone considers cooperative social action (Polanyi 1967, 1991). Some aided by the media may extend this to a wider knowledge of class, race, gender or ethnic structures throughout society, but that would be for opinion leaders, activists or budding sociologists (Strauss 1991).[6]

In the next section, I pursue the process of creating interactional structure more formally.

[1] Mead’s theory of mind deals with impulse, perception, manipulation and consummation. The third stage of manipulation gives humans a much more active role in social action (Joas 2001; Mead 1934). Although manipulation is largely about the model I will present, I will not venture further on his theory of mind.

[2] Jonathan H. Turner also presents a synthetic model (1988:102-117), but the model presented here is quite different. He also focuses on the generalized other but puts more emphasis on Goffman and framing, presenting four types: physical, demographic, sociocultural and personal framing (108-113). These are useful in what I will use later for framing the generalized other; however, he does not point to negative and positive framing, which leads to the ‘we’ and the ‘they.’

[3] I will use quotation marks around the “I” and “Me” because these could be confused with words in the text. This logic also applies to the lesser used “We” and “They.” I will not do so for the GO because the two letters capitalized do not present such a confusion.

[4] The generalized other has been “somewhat neglected” (Holdsworth and Morgan 2007:401) by symbolic interactionists. Evidence of this is further developed in Janoski, Grey and Lepadatu (2006, and 2007) with the development from Blumer to Shibutani of multiple generalized others. Thomas Morrione drew Blumer out on multiple generalized others in an interview (Blumer 2004) where he somewhat reluctantly but eventually admitted that multiple generalized others existed. Shibutani referred instead to multiple reference groups. The Janoski, Grey and Lepadatu (2005, 2006) papers go into this in more detail (see also Yeung and Martin. 2003). However, the latest edition of the Sandstrom et al. (2014) textbook on symbolic interaction does mention multiple generalized others, but they do little to justify or develop the concept.

[5] The Good Place is a TV series on Netflix. Through Chidi it brings a rather large amount of philosophical thinking into a setting with four people who think they are in the good place (i.e., heaven) while they are actually in the bad place (i.e., hell). Putting these people in a so-called ‘good place’ where they do not belong creates a theoretically greater torture than simply sending them to the bad place (Westfall 2019). Ironically, it gives them a chance to escape the bad place.

[6] Other routes to structure are suggested by Sheldon Stryker and Tomatsu Shibutani. Stryker and Vyran (2006: 21) suggest that roles may “imply fixed social structural properties”. However, roles are not organizations with boundaries and “roles” do not act. Instead, groups like one’s generalized other act. Further, roles suggest many of the structural features of functionalist theory. Shibutani (1955) suggests that ‘reference groups’ might take the place of the generalized other and Robert Merton has written extensively on them. This position is very close to a generalized other, but I would like to make a distinction here. Reference groups could be of the anticipated kind (a group that you would like to join and you model your actions to perhaps get into it) and an actual reference group where you interact with others on a regular basis. However, Shibutani’s concept of reference group did not catch on with symbolic interactionists.