For most citizens who are not political operatives, politics is not an all-consuming passion. They tend to get interested around election times, or when there is a controversial issue that piques their interest. Some things that people do are rather continuous like going to work every day or taking care of one’s family and their needs for food, shelter, and transportation. Politics is a secondary interest until there is some event or issue that comes to the fore. And for some people, even then, they are not interested in politics.

As discussed in chapter 10, political parties are voluntary associations whose members voluntarily join and the party itself does not engage people in their everyday decisions. They tend to mobilize around elections.[1] Thus politically and continuously active citizens are the exception and most citizens may monitor the news for political information, but then act in terms of electoral cycles where the more active citizens contribute money, time (campaigning, organizing, protesting, etc.) in addition to voting. A few may be asked for their opinions in candidate’s polls and fewer still participate in scientific social surveys like the America National Election Study (ANES) or the General Social Survey (GSS) scholarly research. Yet most citizens have a fairly clear sense of where they stand on political issues.

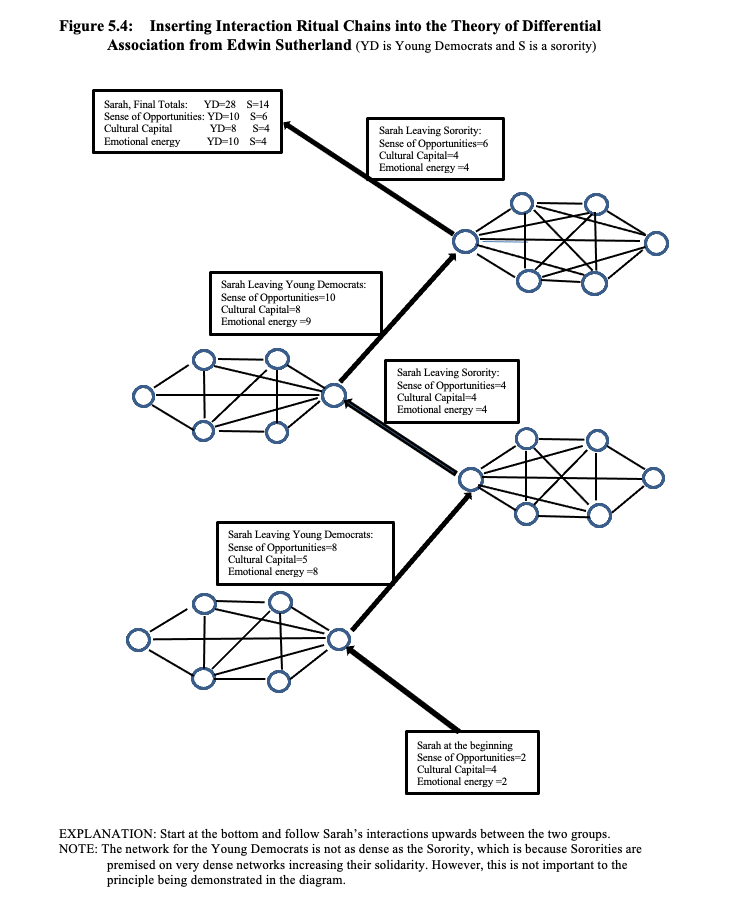

In the following two sections, I shall look at how interaction ritual chains and differential association theory extend the afore described symbolic interactionist theory into political action at the group and structural level.

Interaction Ritual Chains

To present an adequate social psychological theory of how this is done, one has to enter into the group processes involved with symbolic interaction, namely, I have to put the generalized other into action concerning political issues and I will do this using Randall Collins’ theory of interaction ritual chains.

Using the generalized other (rather than the self), a citizen may present a political view that intrigues them and then field the reactions from their audience or generalized other or more simply their social network. This might occur at the dinner table with a family, and the parents may agree, disagree or let it pass. If challenged on the issue, the young citizen then may more cautiously survey their generalized other as to other people’s views on many issues. In early political socialization, sons and daughters mostly accept but some reject their family position on various issues (also, the two parents may be divided). Many children do conform even as they are not particularly interested, or do not understand the issues. As they become more interested with secondary socialization, they are often exposed to different points of view, which they then test out their opinions on their families and peer groups. Other significant groups are involved with religious organizations, which are often active on the restricted and generalized exchange spectrum, and neighborhoods which tend not to be active in giving advice about politics, but nevertheless provide a political context.

Into adulthood, citizens have more choices about their choices of occupations, education, neighborhoods, and so on. This process often occurs through a process of interaction ritual chains (Collins 2005).

Each person enters into such exchanges with a certain amount of emotional energy, social capital, cultural capital, and a sense of opportunity. As they enter into an interaction with others, they meet people with various levels of energy, capital, and expectations and as a result of the interaction they leave it with altered levels of these factors. They may have pleasant interactions with high emotional energy and may sense some common levels of social capital. They seek further interaction with that person. Where they leave with lessened emotional energy (boredom, or unpleasant interactions) with blocked opportunities they may tend to avoid future endeavors. For example. Dorothy Day meets Peter Maupin and they strike it off with a lifetime of activist projects, one being the Catholic Workers Movement. Or other great collaborations may have occurred with Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward. I am telescoping this presentation, and numerous interactions are often necessary to get a full sense of the attitudes, values and sense of self of the other person, but in friendships these items reveal themselves although there may be fits and starts. Thus, through interaction ritual chains as developed by Randall Collins (2004), people figure out with whom they would like to interact.

Differential Association

From simple and repeated or interrupted interactions, citizens develop a stronger sense of attraction and seek out other people who belong to groups. I redirect Edwin Sutherland’s (1942; Matsueda 2001) theory of differential association by replacing “criminal” behavior with “political” behavior and retain the process nature of the theory and come up with nine steps of differential association concerning how people are joining a non-political group or association:[2]

1. Political behavior is learned

2. Political behavior is learned in interaction with other people through continued communications;

3. The more intense learning of political behavior occurs in intimate or intense contact.

4. When political behavior is learned, this includes: (a) techniques of political action (debating, campaigning, giving money, becoming a leader, etc.).

5. The specific orientation of political motives is learned from conceptions of various political ideologies, usually from a political party.

6. A person becomes politically active because of their agreeing more with the political conceptions or ideologies of the group than not agreeing, which comes from interaction ritual chains. The greater the agreement, the greater the activity.

7. Differential association may vary in frequency, duration, and intensity (see emotional energy in interaction ritual chains);

8. The process of learning political behavior by the association with political, oppositional, or apolitical groups involves many different aspects of learning (e.g., in Germany the SDP, the Christian Democrats, or football clubs in FC München; or in the US the Democratic party, the Republican Party or sports bars rooting for ‘da Bears” football team, or a neighborhood book club).

9. While political behavior expresses general interest and values, this does not mean that it is expressed by these values since others who are apolitical may have the same interests and values (but perhaps did not have the same differential action pattern or the same basic socialization).

For example, in Figure 5.3, Sarah Delacourt, a college fresh person interacts between the Chi Omega sorority, which she finds attractive due to their seemingly friendly nature, cool social activities, and interactions with men in fraternities.

But due to some of her values concerning religious communitarianism and sense of caring, she is also attracted to the Young Democrats on campus who express concerns for the poor and disadvantaged, and although not particularly religious have much in common with the Sermon on the Mount. She develops interests in the sorority through rush and finds some of the sorority sisters are quite conservative toward the poor making crude jokes blaming the victim, but many of the Young Democrats are rather hypocritical on these same issues and are simply ambitious for political connections and holding office. She finds that not many of the women in the Democratic group are sorority sisters and make disparaging remarks about them to which she responds that they are not all bigots and that’s there are many caring women among them. Though the process of differential association and interaction rituals chains, she will eventually decide to associate with one group rather than the other. It happens to be an election year, and the differences between the two groups tends to intensify though the groups do not formally interact with each other. Most people will choose one or the other group, though a few may see their mission in life as being a liaison between the two. Eventually, most will build their value system on one or the other group, may choose their major to fit more closely to one of the groups, and will then interact with other groups that are more congenial or in alignment with the chosen group. For instance, the sailing and tennis club may fit better for the sorority, and the ACLU and Amnesty International fit better with the Young Democrats. Again, most people are not looking to be political activists while a majority of students are interested in a lively social life in searching for a temporary or life-long mate. But the interaction ritual chains will be enacted through the larger differential association process through and between groups to create various political groups of participants and some activists. This is the beginning of social structure, and after this “in-group” processes develop through self-categorization and acceptance of many of the group’s norms (Turner 2005).[3]

[1] Communist parties as in China are a bit different since they infiltrate every place of work with co-managers in every firm, bureaucracy and enterprise. From a capitalist point of view, this dual management system is a tremendous waste of time and effort. However, it affords a tremendous amount of political surveillance and control.

[2] This list might seem long and perhaps redundant, but I am following Sutherland’s exact wording as close as possible while changing it ‘criminology’ to ‘political sociology.’

[3] Randall Collins pushes his theory more in the direction of situational rituals with mutual focus and emotional entrainment (2002:47-99). His applications are more situational than group focused, much like Goffman and Simmel (e.g., sexual interaction, situational stratification and tobacco rituals) (2002:223-344). My goal here is connect these interactions with groups and that is why I use Sutherland’s theory.